Facts and Myths about Cape Town’s Water Crisis

Cape Town Mayor Patricia De Lille has announced that Day Zero is now more likely than not. From 1 February, all households have to reduce their municipal water consumption to 50 litres per person per day. The World Wide Fund for Nature has published useful guidelines for preparing for Day Zero. As Day Zero approaches, […]

Cape Town Mayor Patricia De Lille has announced that Day Zero is now more likely than not. From 1 February, all households have to reduce their municipal water consumption to 50 litres per person per day. The World Wide Fund for Nature has published useful guidelines for preparing for Day Zero.

As Day Zero approaches, there are more signs of panic and anger by the city’s residents. It’s understandable, and if the anger can be directed towards resolving the crisis, that’s great. But there are also myths being circulated that need to be debunked.

Myth: Migration from the Eastern Cape is the cause

Recently the technology website Slashdot reported a BBC story that Cape Town is running out of water. One of the most upvoted comments in response blames the drought on migration of “peasants” (the word used) from the Eastern Cape.

The less prejudiced expression of this myth is that population growth is to blame for the water shortage. In a limited sense this is true. If Cape Town had one million instead of four million people, there’d be no problem.

But population growth alone doesn’t explain the water shortage. As the graph below from the City of Cape Town shows, water consumption has stabilised since 2000. In the last year, with increased restrictions and awareness, consumption has dropped considerably.

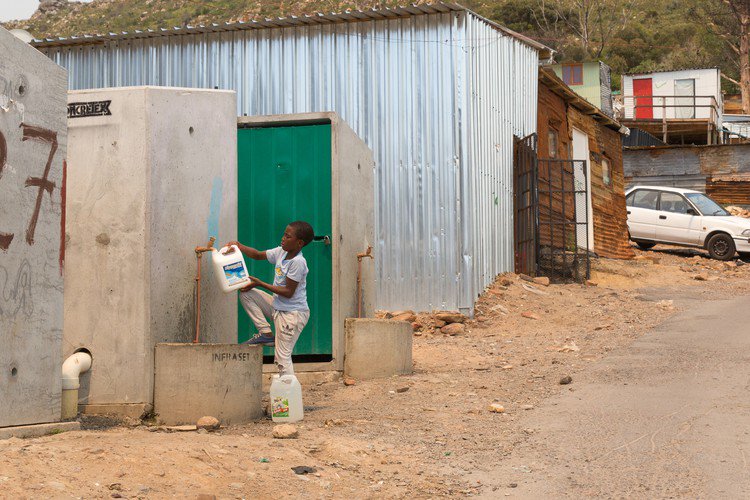

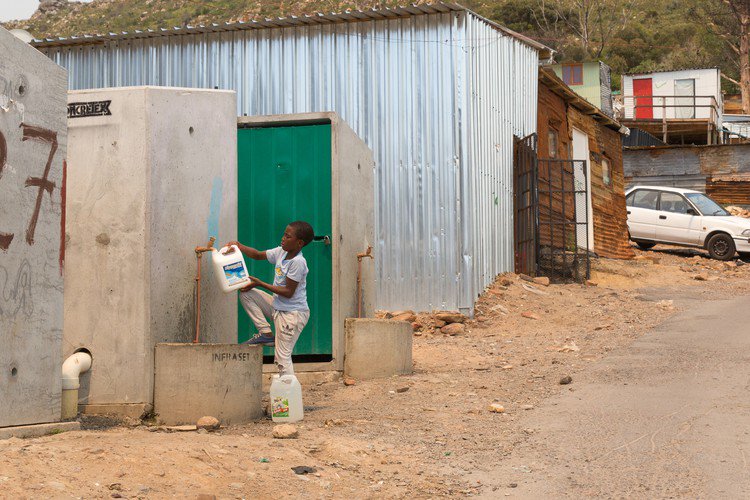

Moreover, people from the Eastern Cape primarily move to the city’s informal settlements. In informal settlements, households generally have to get their water from communal taps; usage is much lower on average than formal households.

Long showers, full baths, maintaining gardens and keeping swimming pools filled are not a common feature of informal settlement living.

Professor Neil Armitage, Head of UCT’s Urban Water Management Department estimates that less than 5% of the city’s metered water is consumed by informal settlements. Formal houses are responsible for 66%. (These numbers may have changed since the article quoting him was written a few months ago as consumption has come down.)

Incidentally, a good deal of the Eastern Cape, including Port Elizabeth, is short of water and enduring water restrictions.

Myth: Farmers are to blame

An article published on the Daily Vox contains a video taken by two Cape Town “vloggers”. The video is sensationalist nonsense and the article uncritical of it. The video shows water from Theewaterskloof being released to farms.

The “vloggers” then throw about misleading statistics about how much water it takes to make a cow, a bar of chocolate, a cup of coffee and other edibles.

Presumably you’re supposed to be so outraged that you immediately march to Patricia de Lille’s office and demand that she puts an end to all farming in the Western Cape. It’s ridiculous.

Agriculture is critical to the Western Cape economy, and the loss of crops, even farms, may be one of the consequences for the city if the dams run dry.

Shirley Davids, spokesperson for farm workers’ union CSAAWU, warns of the loss of livelihoods to farm workers, who will probably be dismissed if farms don’t get enough water.

Jeanne Boshoff of Agri Western Cape sent GroundUp a detailed rebuttal of the video. We’ve included it in full below. But in a nutshell, farms have cut back on their water consumption and they are struggling.

Boshoff writes: “Hundreds of hectares of citrus trees have been cut back and hundreds of hectares of orchards have been pulled out in an effort to save the little water allocated to producers. [This] means smaller yields [and] less food. Indications currently are that the deciduous fruit harvest will be 20% smaller. This means [fewer] seasonal workers will be employed, and for a shorter period of time: an estimated 50,000 seasonal workers will have below normal income or no income at all.”

She also points out: “Grazing and feed shortages resulted in massive culling, causing local red meat supply to tighten, and meat price increases as a result of the drought-induced supply shortages.”

Fact: This is the worst drought in recorded Cape Town history

The main reason for the water shortage is, quite simply, a lack of rain in the water catchment area, probably a consequence of climate change. A lot has already been written on this so no need to repeat it here. Here are articles by UCT scientists that explain the drought:

Complicated: The municipality is ultimately responsible for sorting out the water crisis

Though the municipality is ultimately responsible for sorting out the water crisis, provincial and national government are also on the hook. The Constitution gives municipalities exclusive power over “potable water supply systems and domestic waste-water and sewage disposal systems”, but higher tiers of government must monitor and support development of local government capacity.

And, what is more, they must “see to the effective performance” of municipalities’ water functions.

The Constitution says everyone has the right to access sufficient water. So all spheres of government have a role to play, and constitutional duties in realising the right to water.

The Water Act of 1998 states that the national government is the “public trustee” of the nation’s water resources and must ensure that water is “protected, used, developed, conserved, managed and controlled in a sustainable and equitable manner, for the benefit of all persons”.

It says: “The National Government, acting through the Minister, has the power to regulate the use, flow and control of all water in the Republic.”

The day-to-day management of the city’s water is the job of the municipality, but national government is responsible for oversight. Hence, local, provincial and national government are all accountable.

These articles deal with the national government’s response:

- What national government is doing about Cape Town’s water crisis

- Western Cape needs half-a-billion rand for water crisis

Myth: It’s just a matter of catching the water off Table Mountain

There are no easy solutions to the water crisis. Many measures are needed. Catching the water off Table Mountain is not a trivial measure. The municipality is taking several measures, which are described in What is government doing about Cape Town’s water crisis?

Of course more should be done to use untapped water sources, including catching more water from the mountain before it runs into the storm water system or the sea, but that is not a quick-fix solution.

Fact: The municipality is having a very ill-timed internal fight

The current battle between Mayor Patricia de Lille and others in her party is ill-timed. Cape Town is facing one of its worst environmental crises. Leadership is needed that people can trust. That means that when City politicians and officials provide information on the water crisis we need to be confident that it isn’t spin.

And when the mayor proposes a drought levy, we need to know that her party supports it. Divisions and playing politics with water will be disastrous for Capetonians. The City should put a recognised and respected water expert in charge of all communications on the drought.

Do you have questions about the drought? Email them to info@groundup.org.za and we’ll try to find the answers.

Response to video on Daily Vox by Jeanne Boshoff of Agri Western Cape

Re the video:

A farmer doesn’t use x amount of water to put food on your table. The entire value chain does.

I am not sure why they included coffee and chocolate as examples in the video, because South Africa neither produces coffee nor cocoa beans.

The remark that “vegans make sense”, makes no sense at all since fruit and vegetable production also require water and since both of these industries (in the Western Cape) have been extremely hard hit by the drought and water restrictions. Example: In the Ceres area, the limited water supply resulted in 50% less onions and 80% less potatoes being planted this season.

The impact of this (besides less food being produced), is wage losses of millions of rands for seasonal workers. It may also potentially influence the consumer in price increases. Due to water shortages, two tomato canning factories in Saldanha Bay ceased operations, resulting in thousands of potential job losses.

The factory in Lutzville that produces tomato puree has closed for the season, also impacting on employment. The value chain needs raw product from farmers and if it can’t be provided, in this case because of a water crisis, the negative domino effect is massive on the total community.

4. Hundreds of hectares of citrus trees have been cut back and hundreds of hectares of orchards have been pulled out in an effort to save the little water allocated to producers. Fewer producing hectares means smaller yields, less food. Indications currently are that the deciduous fruit harvest will be 20% smaller. This means fewer seasonal workers will be employed, and for a shorter period of time: an estimated 50,000 seasonal workers will have below normal income or no income at all. Agriculture is the backbone of our province’s rural economies and the effect of the drought can lead to devastating socioeconomic and economic effects. The fruit industry is also the largest contributor, by value, to South African agricultural exports. The industry has a high job-multiplier effect and creates thousands of jobs in the value chain. The industry is also an important generator of very valuable foreign currency inflows, which is now also under pressure.

5. Grain yields in the winter producing regions have been far below average, in some areas 50% below average. In some areas north of Moorreesburg, producers had no yield at all.

6. The red meat producers in the province are totally reliant on drought relief and we thank every member of the public, every institution and every company for continuing to contribute to Agri Western Cape’s drought relief fund, for understanding the important role of farmers in the country and for supporting our producers who supply food and fibre amidst the worst drought in over a decade. Grazing and feed shortages resulted in massive culling, causing local red meat supply to tighten, and meat price increases as a result of the drought-induced supply shortages.

7. South Africa is ranked first on the Dupont Food Security Index’s list of food security countries in Africa. Internationally. We were placed 44th last year, a phenomenal achievement and an improvement of three places despite the drought and despite producers’ water supply being curtailed by between 60% and 87%, and even 100% in some areas. The only people who can get credit for this are our farmers and our farm workers.

Published originally on GroundUp

© 2018 GroundUp.