Makhanda literacy project shows dramatic results

Just 45 minutes a day in a “Whistle Stop School” is helping primary school learners in Makhanda beat South Africa’s alarming literacy statistics. A partnership between an education organisation and a primary school in Makhanda, Eastern Cape, is showing dramatic results in teaching children to read. The “Whistle Stop School” run by community organisation GADRA […]

Just 45 minutes a day in a “Whistle Stop School” is helping primary school learners in Makhanda beat South Africa’s alarming literacy statistics.

- A partnership between an education organisation and a primary school in Makhanda, Eastern Cape, is showing dramatic results in teaching children to read.

- The “Whistle Stop School” run by community organisation GADRA pulls learners out of class in St Mary’s Primary School for 45 minutes a day.

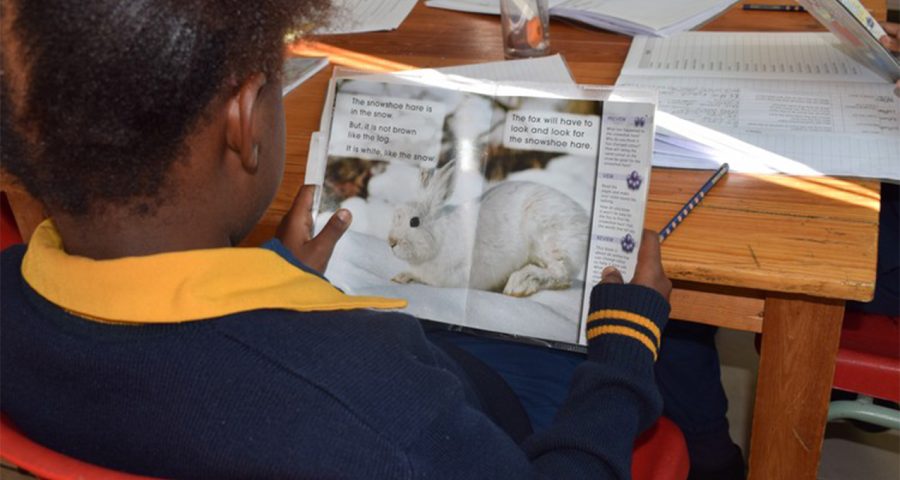

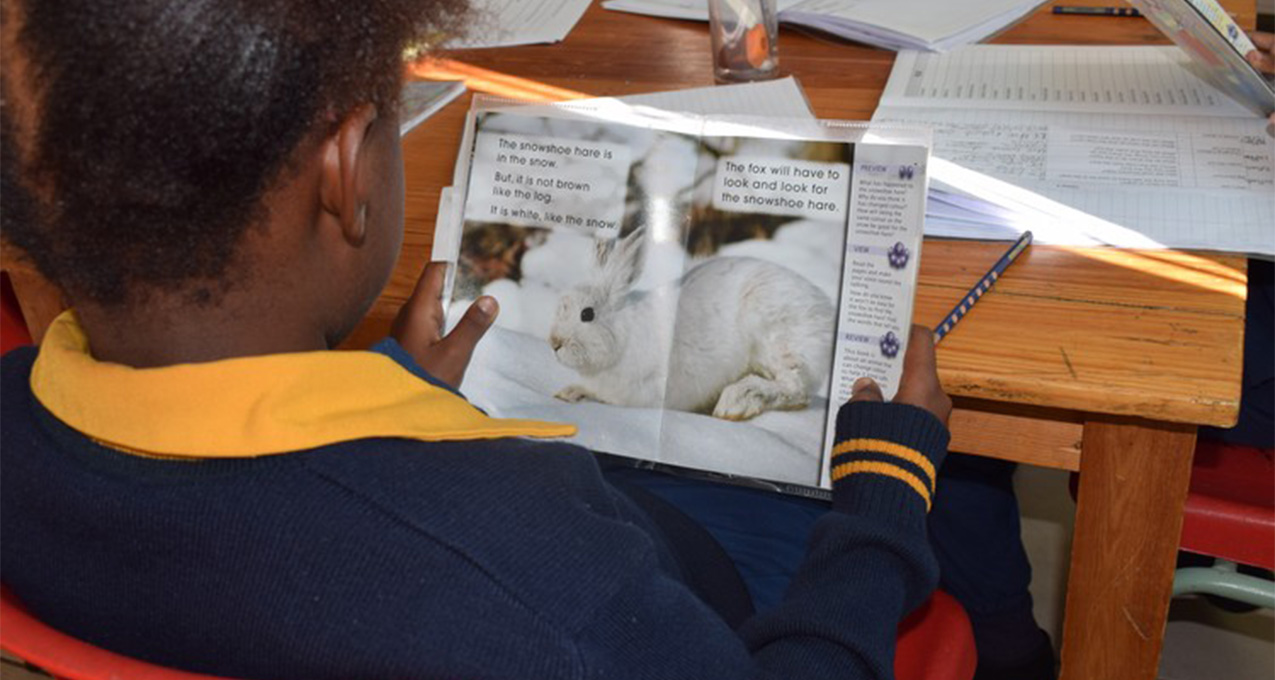

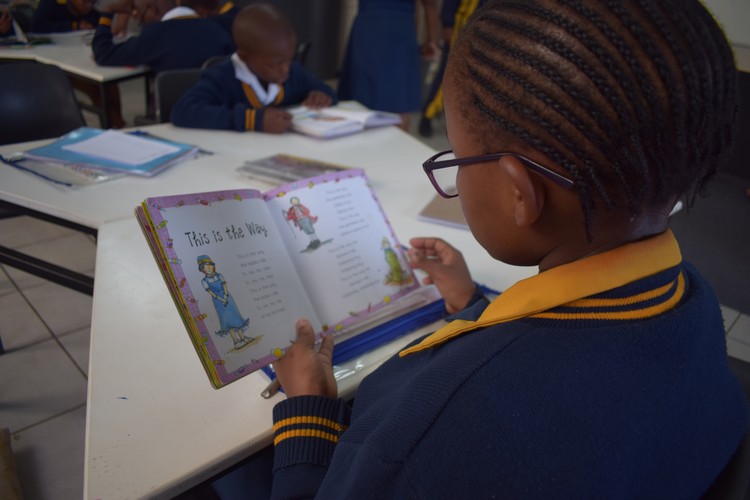

- They are taught in small groups and with access to a wide range of books and learning materials.

- “The results speak for themselves,” said school principal Gerard Jacobs.

- Now GADRA has developed open-source materials for teachers and hopes that the project can spread to other schools.

The Whistle Stop School (WSS) is an early-grade literacy and research programme launched by Makhanda community organisation GADRA Education in partnership with St Mary’s Primary School in 2017. About 12 learners in grades 2 to 4 are pulled out of class for 45 minutes daily for sessions with specialised teachers. The sessions take place in St Mary’s Development and Care Centre, right next to the primary school.

A recent report by the 2030 Reading Panel found that South Africa’s literacy crisis is deepening; 82% of Grade 4 learners can’t read for meaning, up from 78% in 2017.

The National Curriculum Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) stops explicitly teaching reading after grade 3, said Kelly Long, GADRA’s research and communications manager, “so if children don’t know how to read well by the time they get to grade 4 they are going to struggle to catch up.” As a result, many learners are pushed through the system without grasping the necessary foundational skills, said Long.

The WSS programme uses phonics (matching sounds in English with letters or groups of letters), guided reading, and a library to improve the learners’ grasp of reading. Two teachers run the daily WSS classes. “Each sound has its own presentation, which is designed to engage different learning styles. It’s got songs, dance and videos, as well as pictures and things to read,” said Long.

The learners also have access to a well-stocked library where they can take out books at their level of reading, and there are weekly guided reading sessions with the WSS teachers.

“Each week the kids get so excited about the classroom library, it has been incredible to see. We were told we were going to lose books. But in the seven years of running Whistle Stop every week during term, we have lost a total of 19 books,” said Long.

One of the biggest problems teaching reading in schools such as St Mary’s is the pressure to cover the curriculum, said the school’s principal Gerard Jacobs.

“The challenge of a class of 36 learners is that remedial education is not possible. The pressures of curriculum coverage are so much on a teacher. CAPS says you have to cover ABCD by the end of week four, but only around half the class is able to keep up with that ‘normal pace’,’’ said Jacobs, who is also a teacher at the school.

This results in many learners falling behind but still getting pushed through the primary schooling system. By the time many of these learners reach high school “they haven’t mastered the necessary skills to cope,” and end up dropping out, said Jacobs.

The WSS system is quite different. Teachers work closely with small groups of learners, and “we work on the level of the learners’ needs, there is nothing dictated to us,” said Demi Edwards, one of the WSS teachers. And the wide range of reading material enables teachers to work with each child at his or her own level, said Ntsika Kitsili, another teacher. Kitsili said that the one-on-one attention and instant responses from teachers have helped many of the children become more confident, even if they are not always right.

In 2017, the first year of WSS, the 48 grade 3 learners in the project started with a very low reading fluency – at the level of an early Grade 1 learner. This was in line with data from national research, which indicates that most foundation phase learners are reading two years behind their expected level.

After only one year of participation in the project, the grade 3 learners could read and understand nearly double the number of words per minute than before and were at the expected fluency level of grade 3.

Five years after partnering with St Mary’s, more than 75% of each grade 4 class can read for meaning, well above the 20% average in this year’s 2030 Reading Report. This is in spite of the fact that only 40% of the St Mary’s grade 1 class can identify the alphabet, in line with the national average.

WSS has now developed a programme for teachers of grades R and 1, which is being piloted in St Mary’s and in another no-fee primary school in Makhanda. The programme and materials are open sources and free to use – the only cost is a mini projector – and WSS hopes it will help other schools improve literacy levels.

Jacobs said the impact of the WSS partnership with St Mary’s “was seen immediately” in the outcomes of reading tests. Some learners are now reading well beyond the expected level.

“The results speak for themselves,” Jacobs told GroundUp.

Published originally on GroundUp | By Lucas Nowicki