Why are South African companies sitting on R1.8 trillion in cash?

The trend of corporate deposit holdings began following the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, as businesses prioritised liquidity.

South African companies are holding a record amount of money in their bank accounts, according to the latest Quarterly Bulletin from the South African Reserve Bank, raising questions about deferred investment and cautious spending.

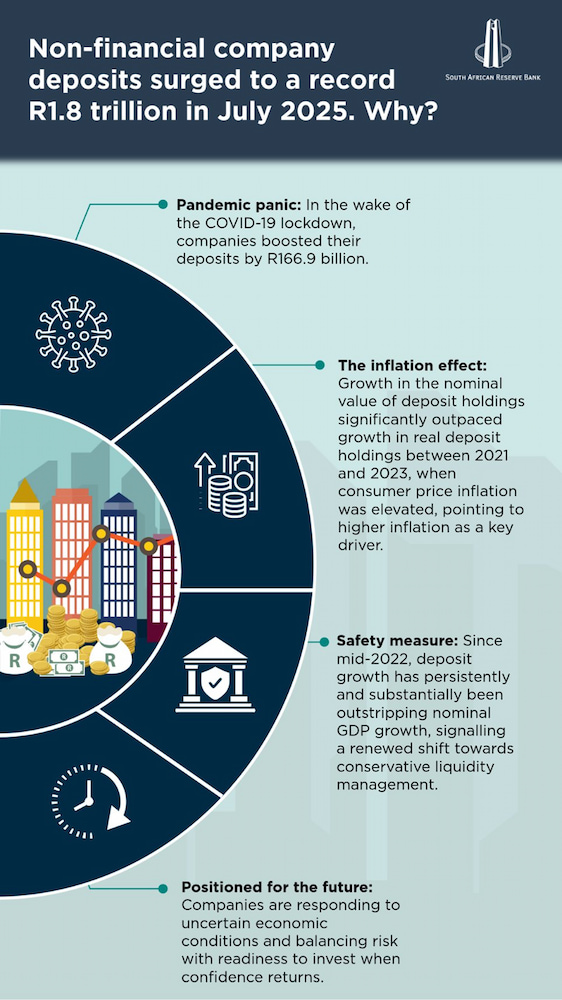

The SARB has revealed that non-financial companies (NFCs) in South Africa held a record R1.8 trillion in bank deposits as of July 2025, detailing the worrying accumulation in its September Quarterly Bulletin. This substantial cash pile indicates a significant shift towards conservative liquidity management amid persistent domestic uncertainty and low economic growth.

The trend of increased corporate deposit holdings began following the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, as businesses prioritised liquidity in the face of acute global uncertainty. The central bank studied this phenomenon, highlighted in the Quarterly Bulletin, to assess whether companies are accumulating excessive deposits or simply playing it safe in a difficult economic climate.

Are South African companies hoarding cash a ‘rational response’?

The SARB’s analysis suggests that the continued rise in deposits is not merely the stockpiling of cash. Instead, companies are making a rational response to prevailing macroeconomic conditions, balancing short-term risks with a readiness to invest once business confidence returns to the market. This defensive stance was clearly visible immediately after the pandemic.

In 2020, non-financial companies increased their deposit holdings by R166.9 billion, driven largely by private firms attempting to strengthen their balance sheets amid acute uncertainty. Although deposit holdings grew further in 2022 and 2023, it was in 2024 that these balances surged again, rising by an all-time high of R186.1 billion.

This pervasive cautious behaviour reflects heightened uncertainty and subdued business confidence across the South African economy.

A crucial detail is the decoupling of savings and investment activities. The gap between corporate deposits and gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) widened sharply from late 2023.

This divergence highlights that while non-financial companies, especially private ones, are sitting on significant amounts of cash, they are delaying major fixed investment decisions due to weak domestic activity and ongoing structural constraints.

CPI and GDP

The discussion around these huge deposit balances must take rising consumer price inflation (CPI) into account. Between 2021 and 2023, elevated CPI suggested that much of the nominal deposit increase was driven by higher prices, rather than a genuine leap in liquidity or savings preference.

Since 2024, however, the growth in deposits has persistently and substantially outstripped nominal gross domestic product (GDP) growth. This reflects a renewed shift toward cautious financial management in a sluggish economy. We note that the South African economy recently expanded at a faster pace in the second quarter of 2025, with real GDP accelerating to 0.8%.

The substantial growth in these deposits has also significantly contributed to the overall broadly defined money supply, known as M3, from 2019 through to mid-2025. The deposits held by NFCs accounted for 31.6% of M3 as of June 2025.

The Quarterly Bulletin also offers perspective on how the accumulation of company money relates to lending. Growth in total money supply (M3) accelerated to 6.7% in July 2025, primarily reflecting faster growth in the deposit balances of companies.

Concurrently, growth in total loans and advances extended to the domestic private sector accelerated to 6.5% in July 2025, driven mainly by the acceleration of credit extended to non-financial companies.

This demand from companies, particularly in sectors such as mining, resources, consumer goods manufacturing, and agriculture, helped boost credit growth. This increase in corporate borrowing, however, contrasts with the subdued growth in credit extended to the household sector, which remains cautious. Overall, the figures paint a picture of non-financial companies prioritising strong liquidity buffers while selectively increasing borrowing for specific operational or investment needs.