Going viral: Ozempic and Mounjaro online

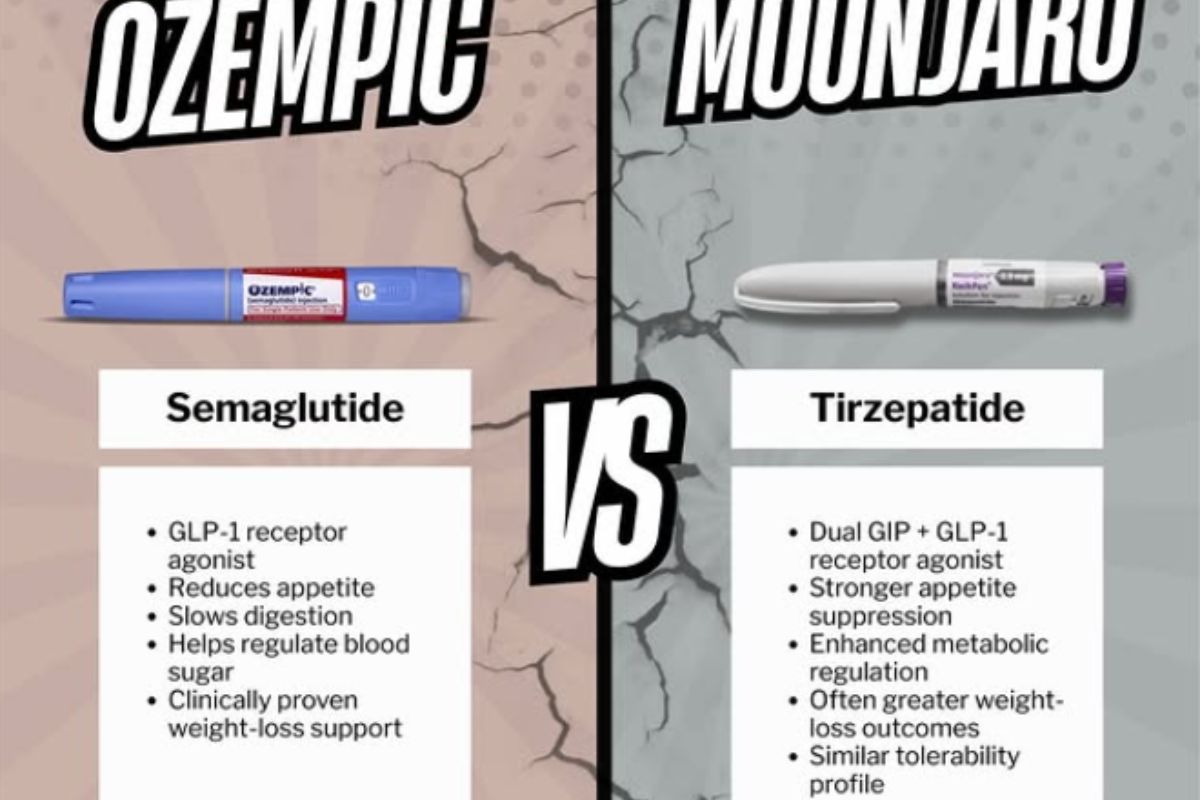

Social media turned Ozempic and Mounjaro into household names, driving many users to seek treatment based on digital trends and influencers.

If you’ve scrolled through your phone lately, you’ve probably seen the videos: people sharing their weekly routines, “before and after” photos, and personal stories about Ozempic and Mounjaro.

These medications were originally made to help people manage Type 2 diabetes, but social media has turned them into a global conversation that reaches far beyond the doctor’s office.

As early as 2026, the data shows that social media hasn’t just talked about these drugs, it has fundamentally changed how many people use them.

How social media changed the conversation

In the past, you would find out about a new medicine from a doctor or a formal advertisement. Today, the conversation about Ozempic and Mounjaro is happening on platforms like TikTok and Instagram.

According to the KFF Health Poll (2025), about 1 in 8 adults in the US have now used a GLP-1 drug. The link to social media is clear: 72% of adults report regularly seeing weight-loss content or ads on their feeds.

When we see something every day on our screens, it starts to feel like a normal part of life, which has helped drive the popularity of Ozempic and Mounjaro to record levels.

The Rise of the ‘Digital Patient‘

One of the biggest shifts is that people are now deciding they want these medications before they even talk to a professional.

- A study published by Dove Press found that roughly 30% of people interested in these drugs made their decision based on “subjective norms”, which is just a another way of saying they saw friends or influencers using them and decided to try it themselves.

- New Ways to Access: Instead of the traditional doctor’s visit, about 17% of users are now getting Ozempic and Mounjaro through online telehealth sites they found through social media ads.

- Nontraditional Settings: Another 9% are accessing these medications through medical spas or aesthetic centers, often influenced by the visual “success stories” shared by others online.

Impact on Public Health and Supply

While social media has made more people aware of their options, it has also created some challenges for the healthcare system.

- The Shortage: Because the demand grew so quickly online, it actually caused global shortages. For a long time, the FDA had these drugs on a shortage list, making it harder for people with Type 2 diabetes to get their essential medication.

- Shifting Demographics: Data from the Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI) shows a clear trend in who is using these drugs. In 2018, 92% of new Ozempic users had a diagnosis of diabetes or pre-diabetes. By 2021, that share had fallen to 77%, and by 2022, only 63% of users had a documented diabetes diagnosis. This indicates that Ozempic and Mounjaro are increasingly being used by people seeking weight management rather than diabetes care.

Understanding the 2026 Data

| Statistic | The Reality |

| Exposure | 80% of women see content about these drugs on social media monthly. |

| Trust | About 1 in 6 people now get health advice directly from influencers. |

| Motivation | Weight loss has become the #1 reason people seek these medications. |

| Awareness | Nearly 1 in 5 adults (18%) have tried a GLP-1 drug at some point. |

A Final Thought for the Reader

The story of Ozempic and Mounjaro shows us just how much power a smartphone can have over our health decisions. Social media has broken down barriers and helped millions of people find new ways to manage their health, but it has also bypassed some of the traditional safeguards we used to rely on.

We are entering a new age of “patient autonomy”. People now take charge of their own health, but they must also navigate a sea of information that professionals haven’t always fact-checked.

We have shifted from a world where the doctor acted as the only gatekeeper to one where the patient acts as the primary researcher.

When we have the world’s medical knowledge – and everyone’s personal experience – at our fingertips, how do we decide which voice to listen to? Does the best advice live in a clinical study, or in the shared experience of someone who has actually walked the path?