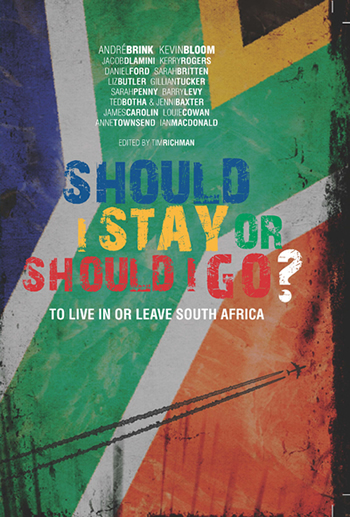

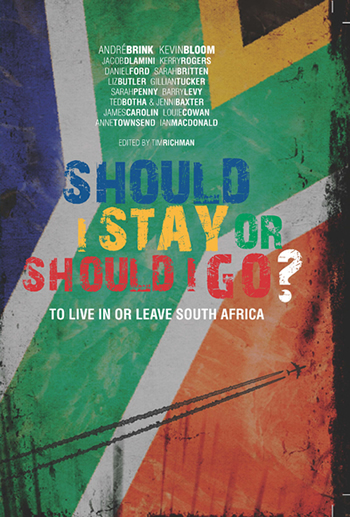

Should I Stay or Should I Go – special excerpt

Here’s a special peek into new book “Should I Stay or Should I Go – To live in or leave South Africa”, taken from the Introduction by author and publisher Tim Richman: This is neither a pro-South Africa book nor an anti-South Africa book. It is a book about emigration in the South African context, […]

Here’s a special peek into new book “Should I Stay or Should I Go – To live in or leave South Africa”, taken from the Introduction by author and publisher Tim Richman:

This is neither a pro-South Africa book nor an anti-South Africa book. It is a book about emigration in the South African context, created both for South Africans who have decided to remain in their homeland and for South Africans who have decided to move on. And it comes, please note, in peace.

Whether you are a till-the-day-I-die stayer, a thank-God-I-made-it-out goer or anything in between, the guiding light in the conceptualisation and creation of Should I Stay Or Should I Go? was one of reconciliation. Or – if that’s a little too close to the political bone in the modern Rainbow Nation – understanding and acceptance.

Readers who fall into the in-between category may be wondering about this early note of caution. Why such diplomacy? Why the reluctance to offend? But anyone who has spent time online engaging in some friendly banter with those on either side of the emigration debate will understand the sentiment. Because, it seems, there is no such thing as friendly banter when it comes to discussing the decision to stay in or leave South Africa. Rather, friendly banter makes way for impassioned and polarised debate – where “debate” is a euphemism for angry and emotional slanging matches in which neither side bothers to listen to the other.

After editing and contributing to Why I’ll Never Live In Oz Again, a title released in 2007 as a somewhat light-hearted counter to the SA-bashing that certain expats are partial to, I became exposed to the ferocity of this great debate raging on the net and at dinner tables around the world. A couple of months after publication I was alerted to an (unremarkable) interview of mine – in which I had suggested that certain expats would do well to get on with their new lives rather than obsess bitterly about the lives they’d left behind – that had appeared on iafrica.com and been linked to a forum on the Homecoming Revolution website. By the time I joined the thread, about seventy entries in, my co-authors and I had been described by various posters as “mummy’s boys”, “failures” and “losers”, for not “cutting it” overseas. I was then informed that should anyone follow my advice to return to South Africa – there was no such advice; none of the posters had read the book – and they were subsequently murdered, their blood would be on my hands. Heavy stuff.

Migration has always been a fact of human life. Until around 10,000BC, when the first human settlements were taking shape in the Middle East, it was a matter of survival – and for some it has remained ingrained in their DNA right to this day. For millennia, people around the world have taken it upon themselves to pack up their belongings and move on from land to land, country to country, seeking fame, fortune, excitement, love, a more pleasant summer climate, nicer people, a better woolly mammoth supply and so on – simply put, a better life. Much of the New World was founded on this notion: America, Australia, South Africa*…

Today, the world really has become a global village, where choice and freedom of movement is almost universal. Relatively cheap air travel connects opposite ends of the world in barely a day, there is a global trade in human skills and international migration has become a fact of life. More than a million people were naturalised as US citizens in 2008. More than half a million people arrived in the UK in 2006 to live for a year or more. In the same year, more than 200,000 Britons emigrated from the UK to live elsewhere (together with just under 200,000 foreigners returning home or moving on). There are more than a million UK-born residents of Australia – to go with 400,000 New Zealand-born residents and 200,000 Italian-born residents. Australia is currently seen as a particularly popular emigration destination, and yet more than 40,000 Australian-born residents emigrate from Australia every year, a number that is rising “as a result of the increasing internationalism of labour markets and global demand for skilled workers”.**

But talking about moving country in the US, UK, Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere surely doesn’t generate such controversy, such sheer emotion, as it does in South Africa and in South African communities around the world. How could it when we have such a troubled, angst-ridden past?

The time I spent online in conversation (and combat) with both leavers and stayers subsequent to the publishing of Why I’ll Never Live In Oz Again opened my eyes to the extent and vehemence of the South African emigration debate. Besides the obvious websites – Homecoming Revolution, South Africa The Good News and the like – it is visible in personal blogs, in reader comments on news sites such as News24 and IOL and even on sports sites such as Keo.co.za.

Essentially, there is a large population of South African expats dispersed across the globe who are struggling to come to terms with their decision to leave South Africa. At the same time, there is a large local population of South African stayers and returnees who have consciously picked their side and feel compelled to defend their decision come what may. Each faction is hellbent on justifying its own position and proving the other side wrong, and the particularly vocal contributors are, predictably, at the extreme fringes of the debate – which is to say, they are completely closed to the alternative viewpoints. If one side says up, the other automatically says down. If one side argues that the sky is blue, the other instinctively argues it is green. Any vaguely ambiguous article – on the state of the global economy, for example – is dissected and declared a victory for both sides. The expats are “racist, bitter and narrow-minded”; the SA defenders are “naïve and blinkered”. There are, it seems, those for emigrating and those against, and never the twain shall meet*. And, of course, they both protest too much. If they were content with their decisions either way, they would simply be going about their lives. But they are not.

A year or so after the publication of Why I’ll Never Live In Oz Again I had come to two conclusions. Firstly, behind the venting extremists on either side of the scale – the vocal attention seekers who seem to dominate so many arguments these days – there must surely be a far larger population of more moderate South Africans looking for an answer. And secondly, the answer they are looking for is an impossible one: they want to know what the right or wrong decision is, when they should be looking for a way to cope with the decisions they have made (or are going to make).

And so the idea for this book came about: a broad take on emigration from a variety of sample points, incorporating pro-leavers, pro-stayers and the various strata in between. A book for people looking for genuine information and empathy – looking for some kind of therapy even – from other people who have been in similar situations.

The pieces compiled here are personal stories; they have to be because the choice of where you live is such a personal one. People think differently, they prioritise differently; they take consolation and umbrage at different aspects of life. As the ostensibly unbiased editor – who has chosen to live in Cape Town rather than Auckland or Sydney – it has been difficult for me to overlook certain comments and opinions. “That’s not right,” I’ve frequently muttered, red pen hovering over an offending line. And yet, to achieve the desired effect, I have had to restrain myself from making “corrections”, because when it comes to emigration no-one is objectively right or wrong. There are, however, misconceptions, doubts and unanswered questions, some of which may be resolved by this book. At the very least, I hope that readers will recognise their own feelings and problems and doubts somewhere along the way, and that the burden of emigrating, or not emigrating, may be shared and dispersed to some degree.

As is to be expected, there are numerous overlapping themes throughout the book: crime and safety, the definition of “home”, the issue of personal identification, the importance of family, South Africa’s uncertain future, the longing for home and love for Africa, and so on. At the same time, despite the shared emotions and experiences, every story is unique. There are fifteen chapters in total, but there could easily be fifty or more because each contributor – and everyone who has ever considered emigrating – has a slightly different set of circumstances, a slightly different perspective. Underscoring each chapter, though, is the desire of the author to make peace with whatever course he or she has chosen; to process and accept the decisions that have been made. Sometimes the peace is made, be it fragile or enduring. And sometimes there is no resolution – yet. But it’s a start.

André Brink’s chapter, written in 2008 after the murder of his nephew, laid an important foundation for this book and, as a result, it begins proceedings. It encapsulates succinctly both the obvious reasons for leaving South Africa – crime and misgovernment – and the less obvious but more heartfelt desire to stay, which is the path he has chosen (though he concedes that he “can never say never”). In justifying his decision, he writes: “A love that can be explained is not love. But the fact that it cannot be rationally explained does not invalidate it.” This is a worthy point, though André underplays his ability to distil into words the emotions that tie so many South Africans to the country of their birth. This piece is an important one for any South African who has struggled to come to terms with the apparent irrationality of staying.

Kevin Bloom furthers this idea in the following chapter, which considers a theme – “South African-ness” – that lurks in the subtext of his excellent debut book Ways of Staying (released in 2009 and described in his author profile and Addendum C). Kevin notes that he writes from a particular point of view, that of the “white English-speaker in post-apartheid Africa”, and he is unapologetic: it was intentional, for he must write what he knows. The point is, though, that he considers himself South African.

Jacob Dlamini contributes the third consecutive piece from an author still living in South Africa. Jacob may not be here for long, though: he is not sure, asking himself the question, “What am I doing in a country that seems to bring out the worst in me?” Having spent a considerable amount of time living abroad in the last decade, he has various options open to him. After an incident of madness one day in northern Johannesburg, he must consider whether his heart is still here.

Breaking from the established format, Ted Botha and Jenni Baxter, co-authors of The Expat Confessions, revisit in a series of e-mails the book they published in 2006. Having received input for it from about five hundred South Africans all over the world, Ted and Jenni are two of the best qualified people to understand the psyche of the SA expat. They offer a broad and insightful overview of “expatdom” while considering their personal scenarios: Jenni is content with her life in Australia, but Ted still considers returning to Cape Town from New York.

Many of the contributions in this book are deeply personal; such is the nature of the topic. For Sarah Britten, there was no other way to approach her traumatic and disastrous emigration experience, one that ultimately destroyed her marriage. Or, as she suggests, perhaps it extended it beyond its sell-by date. Sarah is candid, open, honest, raw – uncomfortably at times. But hers is a necessary and hugely revealing piece, clarifying both the extent of the life-hold that emigration can exert on individuals and families, as well as the stresses it can generate.

The following two chapters shift the focus towards New Zealand, one of our five favoured emigration destinations. Liz Butler is a Kiwi who lived in Cape Town for twenty-six years, where she forged a hugely successful career in the South African magazine industry before returning home to be near her parents. Kerry Rogers is a single mother living in Cape Town who could well follow a similar career path, but who is looking to emigrate to Wellington within the next two years. Despite slipping easily back into New Zealand life, Liz looks back fondly, almost wistfully, at South Africa; Kerry, with a young child to consider, longs for the security of New Zealand. For both of them, as with so many emigrants, their immediate families play a vital role in their decision making. These particular pieces have been included back to back in an attempt to illustrate the subtle (and not-so-subtle) differences of perception and priority between two women who, as ex-Capetonians, could well find themselves living a mere two hundred kilometres apart on the other side of the world within a couple of years. No two emigrants are the same.

An interesting emigration paradox is that of the young families moving in opposite directions: many South Africans leave “for the children”, while many return for the very same reason. As Kerry looks to her safer future in New Zealand, so James Carolin considers his imminent return from Australia with his wife and newborn after ten years abroad. In analysing his desire to go home, it becomes ever clearer that raising their child around family is an absolute priority.

Sarah Penny is another young parent. In her case, though, she has had to adapt to the life of a working mother raising two young children in London. Hers is a beautifully told story of necessity, adaptation and acceptance. Well aware that returning home for good is not an option, she is happy to be surrounded by her young family and content with the life she has made in the UK – and yet a part of her “is always homesick”. As a result, she has chosen to identify herself as a “British-African transnational”, embracing the in-between status that seems to bedevil the lives of so many emigrants.

Barry Levy, an apartheid refugee, is less compromising. He may be in possession of both South African and Australian passports, but after a quarter of a century in Brisbane he still longs for home, and is confounded by the immigrant South African who instantly “reinvents himself as a Wallaby-supporting Aussie”. His chapter is a fascinating look at the depth and durability of what Kevin Bloom might call his South African-ness.

Another long-term expat, Gillian Tucker left South Africa in 1993, making her way to Vancouver Island, Canada, quite literally on the opposite end of the earth. Undertaken for the sake of her young daughter, her relocation was, like so many international moves, almost impossibly difficult to bear. Or, as she puts it, “for most of my first ten years in Canada, I was a certifiable mess.” Yet it was fourteen years before she returned to South Africa for a visit – and by that stage it was almost unrecognisable from her time here, and no longer home for her.

The definition or question of “home” underscores much of the emigration discussion. Anne Townsend is an expat (most of the time) for whom this is a particularly pertinent theme, having spent ten of the past thirteen years abroad teaching English. Taking a break from the traditional emigration destinations, Anne describes her fascinating travels – and life – in the Middle and Far East since taking the momentous decision in her mid-thirties to spend a year in Japan (which she is yet to do…).

A sometimes overlooked emigration “pull factor” is the lure of a foreign love. Louie Cowan survived the sinking of the Achille Lauro in 1994, an incident that inspired him to reach for opportunities he may have previously overlooked. Several years later he found himself living in Chicago, having married a beautiful American girl he met in Italy. After the culture shock suffered in adapting to his adopted country, Louie became a great fan of the American way of life, particularly its attitude of self-improvement. Now divorced, he is content to overlook any homesickness he may have for the sake of his young son.

Ian Macdonald is the young optimist here. As editor of the South Africa The Good News website, he spent five years tracking the fortunes of the country and reporting on them, becoming a visible “pro-South Africa” figure in the emigration debate. As a result he came into the direct firing line of disillusioned expats, an easy target despite the fact that he tempers his positivity with realistic, grounded expectations and concerns. His chapter is adapted from a piece he wrote in 2007 which remains relevant today, especially for young and skilled South Africans pondering their future.

To conclude proceedings, Daniel Ford returns to the question in the title of this book while considering his own return to his native England after thirteen years in South Africa. Since becoming a reborn Londoner in 2007, life has not been plain sailing – but he has dealt with the move because it had to be done. “Maybe it’s time we removed the impossible hang-ups that South Africans have over the ‘Should I stay or should I go?’ question,” he suggests. Indeed.

Tim Richman

April 2010

Cape Town

TO ORDER COPIES OF THE BOOK, PLEASE CONTACT ADMIN@sapeople.COM

Read more about “Should I Stay or Should I Go?”