Big grant for African filmmakers

Two filmmakers from the African continent have been commended by major film bodies for their bold adaptation of an Academy Award-winning film into a true African epic. The Boda Boda Thieves, a film by South African producer James Tayler and Ugandan director Donald Mugisha, has recently been selected as one of five films – out […]

Two filmmakers from the African continent have been commended by major film bodies for their bold adaptation of an Academy Award-winning film into a true African epic.

The Boda Boda Thieves, a film by South African producer James Tayler and Ugandan director Donald Mugisha, has recently been selected as one of five films – out of 113 submissions – to receive a grant from the World Cinema Fund at the prestigious Berlinale Festival in Germany.

The film garnered US$78 330 (R632 000) – the biggest portion of the five – and has also secured funding from the South African National Film and Video Foundation, an organisation that promotes local filmmaking through development and production funding.

It’s an adaptation of Italian director Vittorio De Sica’s original 1948 classic The Bicycle Thieves, which won the New York Film Critics Circle award the following year for Best Foreign Film, and an honorary Oscar in 1950. The Italian version was based on Luigi Bartolini’s novel of the same name.

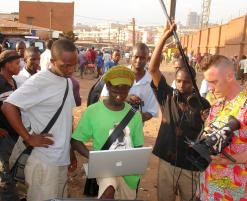

Set in Uganda, The Boda Boda Thieves follows a rural family trying to make a living by running a motorbike taxi – or boda boda – service in a Kampala shanty town.

When thieves snatch the boda boda, and source of income, the family hunts for it through the bustling streets of the Ugandan capital, giving the audience an insider’s view of urban Africa as they go along.

The film is multilingual and contains Luganda, Swahili and Kampala street slang.

According to Tayler, the movie deviates considerably from the 1948 version but aims to stay true to the spirit of the original. “If we try for a remake we will fail, we know this,” he said. “But we are freely inspired by the film.”

Like De Sica’s film, the modern African rendition will stick to its neo-realism roots and will also explore themes about the generation gap, power and survival.

Neo-realism films flourished in post-war Italy between 1944 and 1952. Most stories were set amongst the poor and working class, filmed on location with non-professional actors. The films reflected the changes in the Italian psyche caused by economic and moral upheavals after the Second World War.

Showing Africa to itself

After watching De Sica’s The Bicycle Thieves, Mugisha and Tayler were struck by the similarities between post-war Italy and contemporary Africa.

They studied more films by De Sica and other neo-realists, and were convinced that the digital revolution in filmmaking made it possible, and necessary, to craft realist films that will show Africa to itself.

Setting the story in Africa seemed to be the natural thing to do for the two filmmakers, as they believed the urban areas on the continent are experiencing the same upheavals and restructuring as post-war Italy.

Tayler said Africa is currently re-inventing itself after the colonial era, the various wars of independence and the rise of true democracy.

He added that Africa’s demographics are changing as rural communities flock to the cities. “The fastest rate of urbanisation in the world is taking place in sub-Saharan Africa. Young people from the countryside are seeking jobs in the city.”

Tayler said that they plan to release the film in four-wall screenings in the ghetto video halls and other venues, as well as at an international world cinema festival. A four-wall screening is one which can take place in any space with four walls, seating, and appropriate sound and projection – in other words, a church or community hall, a library, or even an actual movie theatre.

Applying ubuntu to filmmaking

Tayler works with the Yes! That’s Us collective, an NGO that applies the principles of ubuntu to filmmaking. Tayler said the collective “aims to steer African cinema towards autonomy and a sense of self that is rooted in who we actually are”.

He added that the NGO is a pan-African statement that has a philosophy and encourages collaboration. “We credit our films directed by Yes! That’s Us in deference to the role played by the collective in realising them,” he said.

The NGO has already produced and released two films; Divizionz and Yogera.

Tayler is optimistic that the new creative energy and talent that abounds in the South African film industry will help develop local cinema.

For the industry to grow, he believes that local filmmakers have to open up to the rest of Africa and forge new partnerships. “We are missing enormous opportunities in the rest of Africa. We hope to position ourselves out front,” he said.

He also said that South African cinema will grow like any other film industry, by stumbling a few times before becoming successful. “We need to make a lot of bad films before the really great ones will emerge.”

The story comes first

Yes! That’s Us is currently pioneering a filmmaking technique called the GueREAListic approach – the name is taken from the guerrilla freedom fighters that liberated Africa. Film units are divided into small groups of people performing a number of tasks without a centralised command chain.

The NGO does not punt a director’s agenda and instead insists that the story comes first.

“Everyone contributing to the finished film has ‘directed’ the film in one way or another. All that matters is the story and its connection to the audience,” said Tayler.

The mandate also asks filmmakers to put Africa first, urges them to own their equipment, advises to not feed Western preconceptions of the continent, and encourages collaboration with other artists from other platforms such as music, dance and even fashion in order to make better films and broaden the audience.

Source: www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com