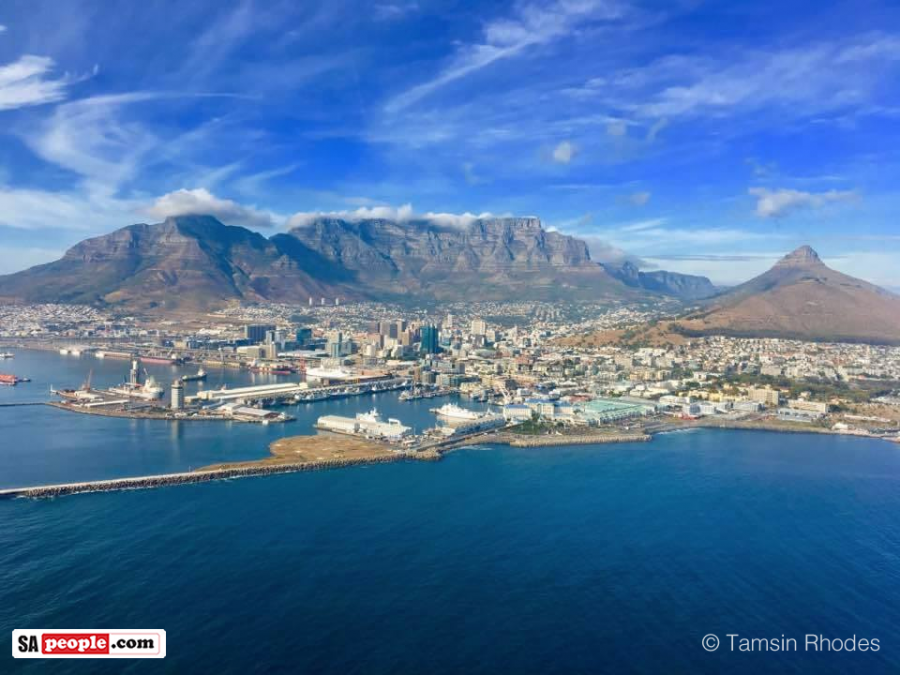

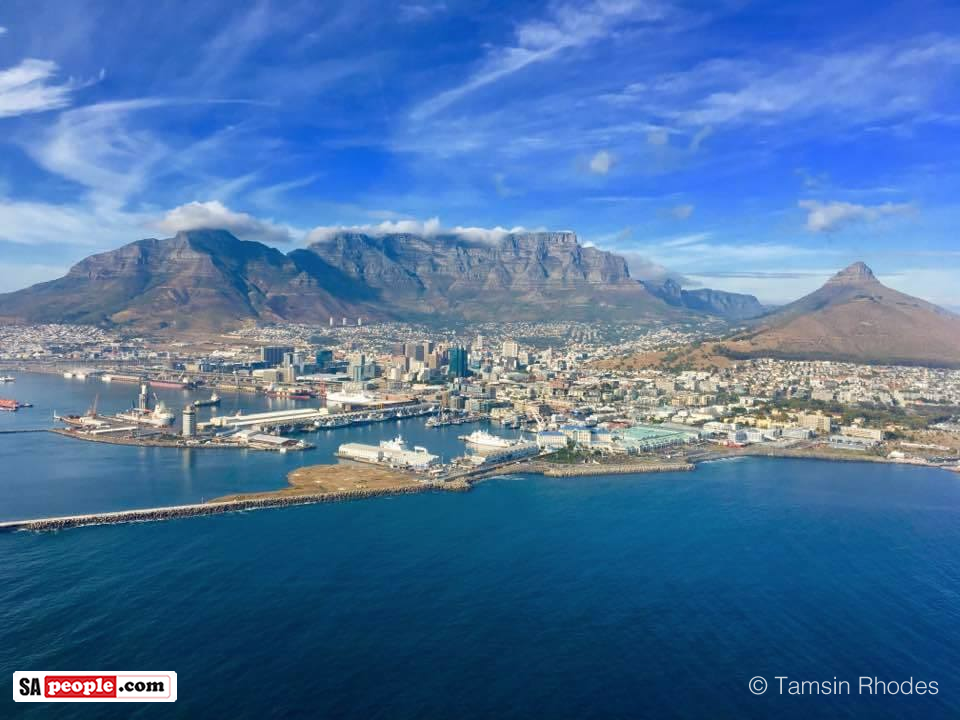

City of Cape Town Answers Your Desalination Questions

With a city in the rare position of being located besides not one – but two – oceans, Cape Town, South Africa, has come under fire for not having desalination plants in place… and several rumours have been posted and shared on social media about the City’s alleged lack of foresight and resistance to Israel’s […]

With a city in the rare position of being located besides not one – but two – oceans, Cape Town, South Africa, has come under fire for not having desalination plants in place… and several rumours have been posted and shared on social media about the City’s alleged lack of foresight and resistance to Israel’s offer to help, after it drought-proofed its own country with large scale desalination plants. SAPeople sent some of your most asked questions to the City of Cape Town, and Alderman Ian Neilson, Deputy Mayor of the City of Cape Town, South Africa, has kindly responded below:

1. What is the current status of desalination plants for Cape Town – when will they be coming on stream, and how many litres per day will they provide?

Overall, the City can confirm that it is focusing in the short- to medium-term on three modular reverse osmosis desalination plants, as well as on aquifer abstraction and water recycling.

The V&A desalination plant (two million litres per day) is due to start producing water by March/April 2018. We are still on track for this.

The Strandfontein project (seven million litres per day) is due to start producing water from March 2018.

The Monwabisi project (seven million litres per day) has been delayed to facilitate further community engagement in the area. The plant was due to start producing water by February, but four weeks of construction time has been lost to date. With the support of the community, the City is all hands on deck to get this project going again and to make up for delays.

After advice from the World Bank, the City has shifted focus from desalination to optimising the use of aquifers in the short term, as this is more cost-effective and quicker to implement than temporary desalination plants.

The Cape Flats aquifer will deliver 80 million litres per day, the Table Mountain Group aquifer will deliver 40 million litres per day, and the Atlantis aquifer will deliver 30 million litres per day over the period from 2018 to 2020.

The groundwater abstraction projects form part of the City’s programme to supply additional water from desalination, water recycling and groundwater abstraction.

Abstracting groundwater in bigger volumes means the City can deliver more water at a lower cost for the benefit of all residents of Cape Town.

2. Why did Cape Town allegedly reject Israel’s offers to help with desalination plants?

The City is not aware of this offer. This is a widespread misapprehension.

The City has consulted with various role-players in the desalination industry with respect to informing tender specifications for desalination plants. Any company, both local and international, is required to participate in a competitive tender process.

Whilst we appreciate the many solutions being offered to us, we cannot deviate from the legally prescribed tender processes. All companies that apply through these processes are scrupulously evaluated in order to ensure that their offering is suited to our requirements, and is not prohibitively expensive.

3. Why were desalination plants not installed years ago?

The City has had programmes in place since 2000 to reduce demand and conserve water.

This has been an unprecedented and quite unique situation primarily because of the long-unfolding nature of this particular crisis. Most of us see a crisis as an event which happens devastatingly fast, such as a massive hurricane or other defined natural disaster. But this drought has had a very different nature.

As we enter a phase where a disaster, as most people understand it, is tangibly looming if we do not all reduce consumption immediately (and there is a lot of room to reduce usage according to our statistics), it is an expected response to level blame.

Constitutionally, National Government is the custodian of water resources, i.e. for ensuring the availability of bulk water supply so that the water authority can distribute it. It also is responsible for directing the usage of its users, such as urban users and agriculture. But, as for urban usage, local governments must ensure that it is able to distribute bulk water from bulk water schemes via the reticulation networks to water users. To do this, the Constitution prescribes that municipalities must ensure that water losses are reduced through investment and maintenance of infrastructure and that conservation is key, among other factors.

All spheres of government must collaborate for the model to work and collaboration has been key.

From the City’s side, the following must be noted:

“there has not been that much said about what actually was done by authorities in those years to address the warnings about water scarcity in the future”

There has been much discussion over whether or not a drought of this magnitude (scientists refer to it as being the worst recorded drought in the region in the past 400 years) could have been foreseen amid allegations of warnings some 15 years ago or more.

However, there has not been that much said about what actually was done by authorities in those years to address the warnings about water scarcity in the future.

Since 2000, the City has adopted a strong conservation and infrastructure-led approach to water management.

This was the immediate response borne out of water-scarcity projections.

Despite our population growth almost doubling since 1996, our water demand has remained relatively flat.

From 2000, the City started implementing aggressive pressure management technology, infrastructure maintenance, and public education initiatives to drive water conservation and water demand management.

This strategy was internationally recognised for its success at the 2015 C40 Cities Awards in Paris where it was acknowledged as the best in the world in terms of preparing the city for the possible challenges of climate change.

The City has also always been ahead with the implementation of water restrictions as a proactive step in managing water in a water-scarce region such as Cape Town.

Over many decades, engineers and planners have built the water supply infrastructure in the city and in the surrounding areas, which continues to serve us well. This infrastructure and the associated water management techniques have previously navigated Cape Town through drought periods.

The drought we are currently experiencing, however, is the most stubborn, intense and protracted in recent history.

Restrictions must be imposed on abstractions from surface water supply schemes during periods of drought. The water system modelling is undertaken by the National Department of Water and Sanitation and they define the level of restrictions required.

It is worth noting that the City and surrounding municipalities voluntarily imposed water restrictions by January 2016 before being officially required to do so out of concern due to the very low 2015 winter rainfall.

Prior to the onset of the drought, the City was using water well under its registered allocation from the bulk water schemes.

Over the years, we have, among other measures, pooled management of our own Wemmershoek and Steenbras dams with the larger National Government dams to maximise system yield for the benefit of all users; we have fully financed the Berg River dam to improve water security; substantially reduced water demand to delay investment in expensive water infrastructure; contributed to the operation and management of the water system through payment of raw water and catchment management charges; and voluntarily reduced abstractions from the Voёlvlei Dam to ensure water security for the West Coast municipalities in 2016 at our cost.

In addition, we remain active and committed participants in the Reconciliation Strategy Steering Committee convened by the National Department.

Rainfall is a notoriously difficult climatic phenomenon to predict. Even the best scientists internationally and nationally could not predict these extremely abnormal climatic conditions.

The operating system in a drought, across the world, is that one does not respond to a normal drought by building more expensive water schemes.

Rather, to protect water users from being saddled with the hangover of unaffordable infrastructure when the climate normalises again, water demand and conservation management remains key.

This strategy has been reinforced by strong communication efforts to drive down consumption.

The adage goes that one makes the best possible decisions based on the best possible information that is available at a given point.

The City has followed this approach based on the vast technical and operational skills that it has in its arsenal. Not for a second have we ever made a decision in this complex hydrological environment that has not had the best interests of our residents and businesses at heart.

In fact, we have a vested interest in having our city thrive and having it become a more resilient city.

We therefore implemented a proactive stance to management of our water allocations. Our overall water losses is 16% versus 36% of the national average – no mean feat for a metro the size of Cape Town. We introduced innovative engineering initiatives, such as advanced pressure reduction at our bulk water reservoirs and reticulation systems in an effort to drive down water demand.

As we are an administratively strong city, we managed to draw high user data and embark on a campaign to restrict excessive users.

This, along with our sustained communication campaigns, has seen a reduction in usage from 1,1 billion litres of water per day to the current 600 million litres per day. It has taken a mammoth effort to achieve the level of behavioural change that we have achieved thus far.

Alternative water resources have been carefully studied by the City over the years. As the abnormal climatic conditions relentlessly continued, the decision was made in May last year to expand the City’s mandate further to diversify our water supply in order to augment the use of surface water from the national department’s surface dams and increase our bulk water allocation. The City is currently implementing various small-scale augmentation schemes to achieve this.

This includes desalination, aquifer abstraction and water recycling.

***

Carte Blanche recently broadcast a highly praised in-depth investigation into Israel’s desalination. Watch the teaser below or subscribe to watch the full episode (and more) here.

How did Israel go from being a water scarce country to having more water than they could ever need? @Devi_HQ looks at Israel’s large-scale #desalination plants and asks: can the rest of the world learn from this ingenuity? #CarteBlanche Sun 7pm pic.twitter.com/by5LgI12B6

— Carte Blanche (@carteblanchetv) January 11, 2018