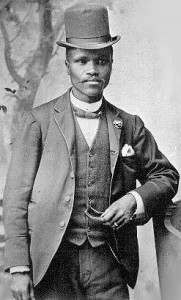

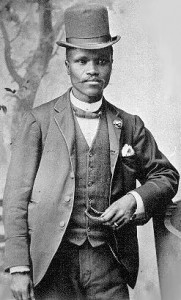

Remembering Enoch Sontonga

Enoch Mankayi Sontonga, a teacher and lay preacher from the Eastern Cape, died in obscurity 106 years ago today, aged just 33. But he left an indelible legacy. His hymn “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” (God bless Africa) went on to become the continent’s most famous anthem of black struggle against oppression. Sontonga wrote the first verse […]

Enoch Mankayi Sontonga, a teacher and lay preacher from the Eastern Cape, died in obscurity 106 years ago today, aged just 33. But he left an indelible legacy.

His hymn “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” (God bless Africa) went on to become the continent’s most famous anthem of black struggle against oppression.

Sontonga wrote the first verse and chorus of “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika”, a prayer for God’s blessing on the land and all its people, as a hymn for his school choir in 1897. Later in the same year, he composed the music.

The famous song has since been reworked and adopted as South Africa’s national anthem, translated into numerous African languages, including Swahili, and incorporated into the national anthem of Zambia, Tanzania and Namibia.

On 8 January 1912, at the first meeting of the South African Native National Congress, the forerunner of the African National Congress (ANC), it was sung after the closing prayer.

Solomon Plaatje, a founding member of the ANC, first recorded the song in London in 1923, accompanied by Sylvia Colenso on the piano. In 1925 the ANC adopted the song as the closing anthem for their meetings.

The song was published in a local newspaper Umthetheli Wabantu on 11 June 1927, and was included in Incwadi Yamaculo ase-Rabe, the Presbyterian isiXhosa hymn book, as well as a Xhosa poetry book for schools.

Seven additional stanzas in isiXhoza were added by the poet Samuel Mqhayi, and a Sesotho version was published by Moses Mphahlele in 1942.

Popularised at concerts in Johannesburg by Reverend JL Dube’s Ohlange Zulu Choir, “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” was later adopted as an anthem at political meetings.

Prior to South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994, the country’s official anthem was “Die Stem van Suid Afrika” (The Call of South Africa), composed by Afrikaans poet CJ Langenhoven in 1918. “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” was the unofficial anthem, sung by the majority of the population.

In 1994, the two anthems were amalgamated into one through the talents of a team of South African music experts, including renowned composer and choral director Prof Mzilikazi Khumalo, and Jeanne Zaidel-Rudolph, currently Professor of Composition at Wits University’s music school.

Searching for Sontonga

Although Enoch Sontonga had become a national treasure in the years after his death, and especially after 1994, the location of his grave remained unknown for nearly a century.

An act of vandalism at Johannesburg’s Braamfontein Cemetery helped locate the grave, ending months of detective work by Johannesburg officials, archaeologists and historians.

The search started by chance at a dinner by the National Monuments Council in honour of then-President Nelson Mandela, in Cape Town in late 1995.

A relative of Sontonga’s who was present told Mandela that Sontonga was believed to be buried somewhere in the Braamfontein Cemetery. Mandela called for a memorial to Sontonga in the cemetery, to be erected in time for the first post-apartheid Heritage Day, which takes place annually in September.

The National Monuments Council instructed the Johannesburg Parks and Technical Services Department to investigate, but finding the grave proved far from simple. It took project manager Alan Buff almost nine months of intensive research – a lot of it in his own time – to locate the exact spot.

One problem was that in the early 1970s, the city council covered much of the long-disused cemetery with a metre of soil, and grassed it over, hiding all traces of the older graves. Another problem was that although records of several graves under the name of Sontonga could be found, no grave could be found under “Enoch Sontonga”.

A suggestion that Buff search under “Enoch” proved correct: grave number 4885 was revealed, buried in the Christian Native section on 19 April 1905. Sontonga had died unexpectedly the day before, of gastro-enteritis and a perforated appendix.

“It was a common cause of death at the time,” said Buff. “The water wasn’t very safe.”

Sontonga’s death was confirmed by a notice found in the newspaper Imvo Zabanstundu.

The Christian Native area consisted of three sections covering 10 acres, with 600 graves – but the plan for that section of the cemetery was missing. This called for sharp detective work.

Buff scanned all the registers and eliminated sections one by one until he arrived at an L-shaped plan within which Sontonga was likely to be buried.

Infra-red photographs, taken in 1979, indicated long-covered grave shapes and pathways.

Professor Tom Huffman of nearby Wits University’s archaeology department was called in to do a shallow excavation to help establish the precise burial spacing.

This helped narrow down the likely area to a 40 square metre triangle containing 33 graves. But this still didn’t answer the question: where exactly was grave 4885?

Vandalism and lateral thinking

“At the end of February, in the middle of my investigations, vandals removed tablets from the cremation wall,” said Buff. The vandalism prompted him to take a look at documents from the cremation section of the cemetery – which he had not considered before – and there he discovered a plan of the cemetery.

“It was the original cemetery plan and showed the starting point of the section where Sontonga was buried.”

The Wits dig uncovered a grave number plate with 17 inscribed as the last two digits, with a faint 4 preceding the 17. A check of the register showed that a number ending in 417 was situated four graves away in the same row as 4885.

Further checks of the registers and plans revealed discrepancies and inaccuracies in the original plans. But the final clue was that the family had registered for private rites, which gave them the right to erect a headstone at the grave.

The Wits archeologists were called back to excavate further, and although no actual headstone was found, the mark of a headstone was visible. This had to be the site.

Memorial: reflections

By this stage the National Monuments Council had formed the Enoch Sontonga Committee. On Heritage Day, 24 September 1996, a large, striking black granite cube was unveiled on Sontonga’s grave, and the site was declared a national monument.

At the ceremony, the Order of Meritorious Service in gold was bestowed on Sontonga posthumously, accepted by Ida Rabotape, his granddaughter. This award was given to citizens who served their country to an exceptional degree. It was replaced in 2002 by the National Orders.

The granite cube placed on his grave was designed by architect William Martinson, and is meant to signify reflections, especially as one moves closer to the monument and one’s image becomes visible.

Nelson Mandela unveiled the monument, and said: “By the pride with which we bellowed your melody and its lyrics – in good times and bad – we were saying to you, Enoch Mankayi Sontonga, that with your inspiration, we could move mountains …

“In paying this tribute to Enoch Mankayi Sontonga, we are recovering a part of the history of our nation and our continent … Our humble actions today form part of the re-awakening of the South African nation; the acknowledgement of its varied achievements.”

At a ceremony in 2005 to mark the centenary of Sontonga’s death, then-arts and culture minister Pallo Jordan appealed to the country’s writers, artists and composers to deposit copies of their work with the National Archives, since “we all have the responsibility of preserving our heritage”.

Jordan was lamenting the loss of Sontonga’s exercise book in which, it is believed, he recorded many of his songs.

Sontonga’s exercise book was lent out to other choirmasters and eventually became the property of a family member, “Boxing Granny”. She never missed a boxing match in Soweto, hence the nickname. She died at about the time Sontonga’s grave was declared a heritage site in 1996, but the book was never found.